As the coronavirus pandemic drags on, it's now increasingly apparent that 2020 will be remembered for an unusually high death toll -- not just from COVID-19. In the medical field, deaths above what you would normally expect are called "excess deaths." Even after you subtract out COVID-19 casualties, many thousands more Oregonians, Idahoans and Washingtonians have gone to an early grave this year compared to a typical year.

The average number of deaths over the prior three years gives epidemiologists a pretty good idea what to expect if 2020 were a normal year. But we know it's not a normal year. Something about this pandemic -- or more likely a combination of things -- is causing significant collateral damage not captured in the widely publicized COVID-19 death toll.

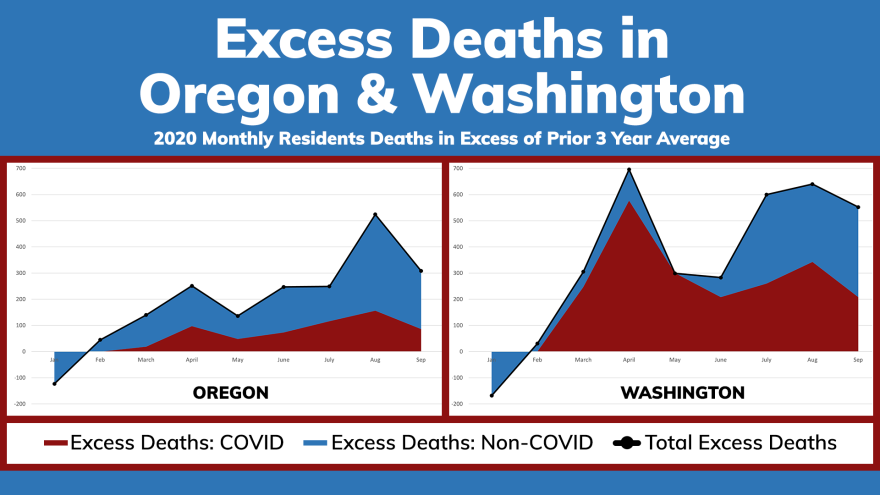

There have been nearly 2,000 deaths above normal this year through October in Oregon, around 3,300 deaths above normal in Washington state and 1,100 in Idaho, according to preliminary data collected by the federal Centers for Disease Control and the Oregon Health Authority. All of these numbers are subject to adjustment based on lagging death certificate filings.

The current figures represent about 7% more deaths than normal in Oregon, about 10% higher than normal in Washington and 13% higher in Idaho for the year to date. Oregon attributes fewer than half of its excess deaths to COVID, while COVID accounts for more than half in Washington and Idaho. Abnormally high numbers of casualties from all other causes stand out from July onwards in the Pacific Northwest.

Some of these could be unrecognized COVID-19 deaths. State health officer Dr. Kathy Lofy of the Washington Department of Health gave the example of a respiratory infection that aggravates an underlying heart condition.

"It kind of looks like a cardiac-related death, but it's really the infection that sort of triggered the exacerbation and the cardiac status," Lofy said.

Many area hospitals have started universal COVID-19 testing of every patient admitted to catch undetected coronavirus cases, said a Washington State Hospital Association spokesman.

Fatal drug overdoses are up this year in most places around the Northwest and the nation, according to county and state health departments and the American Medical Association. Lindsey Arrington founded the Snohomish County, Washington-based nonprofit Hope Soldiers to help people overcome addiction and depression.

"I've seen the numbers rise over the years, but they exploded this year quite a bit because of isolation, because of not being able to have the lifeline to in-person contact especially with 12-step meetings, support groups and friends," Arrington said in an interview Monday.

After the pandemic hit, Hazelden Betty Ford centers and other treatment providers started offering virtual addiction and mental health treatment in Washington state and Oregon. Arrington said that's good, but not a full substitute for 12-step meeting fellowship.

"Not everybody is savvy with that," Arrington said about the online rehab meetings. "And there's something about the energy in a room full of people that you relate to that is a lot different than on a screen with a bunch of people you relate to."

"Until more data become available, it is premature to say how much of the spike in overdose deaths is attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic," said Dr. Tom Jeanne, Oregon deputy state health officer and deputy state epidemiologist, in a statement.

An alternative explanation for the spike is an influx of potent, illegally manufactured fentanyl and methamphetamine this spring. As little as 2 to 3 milligrams of fentanyl can kill a person, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Fentanyl shows up in counterfeit pills or laced with other illegal street drugs.

Loneliness, loss of health insurance and delayed care

Several other possibilities are not direct causes of death, but have been shown in medical studies to raise death rates. One is increased loneliness and isolation, especially among the elderly. In the Pacific Northwest, among non-COVID causes of death tracked by the CDC, Alzheimer's disease and dementia had the highest number of deaths above normal since February followed by cancers. Caretakers of late-stage Alzheimer's and dementia patients said the disruptions of the pandemic caused a more rapid decline for some who were fragile to begin with.

A different factor could be loss of health insurance from the waves of layoffs that began in March. The Urban Institute recently forecast that around 10 million Americans will lose employer coverage by the end of this year.

But the most frequently cited reason Northwest health experts gave for the surge in non-COVID deaths is delayed care. Some of this is probably due to people being leery of going to the doctor lest they be exposed to the coronavirus. Also, many elective surgeries were delayed in the spring to preserve hospital capacity, a phenomenon which is now cropping up again.

"Our emergency room visits have still not recovered to pre-COVID levels," said Dr. Elizabeth Wako, chief medical officer at Swedish First Hill medical center in Seattle. "They are down by 25%-30%. So, imagine all of those people who are no longer going into the emergency room. This doesn't mean they're going to urgent care. They might not be going to see their primary care provider. They are staying at home and potentially passing away at home when they should have come in to the hospital."

Wako said avoidance of the doctor's office and regular screenings is also catching up to cancer patients.

"We've seen patients presenting with late-stage disease. That is just starting to show up now," Wako told reporters during a videoconference last week.

Across the mountains, Dr. Andrea Carter is a primary care physician and chief medical officer with Samaritan Healthcare in Moses Lake, Washington. She too connects the unusually high number of deaths from all causes -- the "excess deaths" -- to people waiting to seek care until they are really sick.

"When we finally did have people coming back to the clinic to see us, it wasn't routine care," Carter said. "It was much sicker people coming to see us, which they identified as routine care. I'm sure that has contributed."

Hospital clinicians reiterated during the media videoconference: if you've got a pressing health problem, do not put off getting it looked at. Especially if you need immediate medical attention, go to the hospital or urgent care. The doctors insisted it is safe to come to the hospital.

Arrington, the president of Hope Soldiers, said she likes to remind people that humans are "a resilient bunch" and equipped to overcome big obstacles together.

"This year has been very dark and heavy," said Arrington, who is ten years into recovery from drug addiction herself. "So, it is important to remember that going into this season, going into December, there is a lot of light still left in this world. There is a lot of beauty, goodness and love still left in this world. If we have it inside of us, we must share it."

This story has been updated.